The public or private activities of foreign trade operators are affected by periodic reviews of the Harmonized System (HS), which are certainly essential and predictable. Although the most recent revision came into force earlier this year, the correlation of HS versions is an ongoing issue in preferential trade.

When correlating the subheadings of two versions of the HS, different alternatives are presented:

• One to one: The simplest case is when a subheading in the previous version of the HS is equivalent, in the new version, to a single subheading in a one-to-one relationship.

• One to many: A subheading in the previous version splits its content into two or more subheadings.

• Many to one: Several subheadings of the previous version can converge in a single subheading of the new system.

• Many to Many: Finally, several subheadings of the previous version are distributed among a group of subheadings of the new version.

• All these equivalent openings of the new version can be existing subheadings or, on the contrary, be subheadings created in the new version.

In the different alternatives – except for the first case – the products contained in a tariff opening of the previous version were subdivided or mixed with products from other openings. These changes have something in common: the universe of inputs or products included in the converted tariff opening is different from those contained in the previous version.

In origin, recall that a rule based on a change of tariff classification requires that inputs classified within the scope of the classification change must be originating. This is very important because if any such input is “non-originating”, the product produced with it will also be “non-originating”.

Therefore, if we only make the correlation between the versions of the HS that arise from the tables prepared by the WCO, and do not take into account the changes in the composition of the subheadings, we will be distorting the requirement of the rules of origin as they were negotiated, altering the restrictions between non-originating inputs and final products.

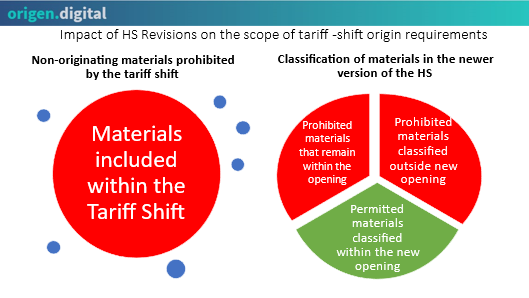

Why do we say there is a distortion? Let’s see this impact through an example and its corresponding graphical representation. Let’s suppose:

• Heading A of the previous HS version is equivalent to heading B of the new version.

• The requirement of the rule of heading A is change of heading.

• In the graph, the red circle on the left represents the five inputs or products classified in heading A that are restricted by the rule of origin.

• When making the correlation with the new version, it may happen that four of the inputs pass together to item B of the new SA (see the red triangle “Prohibited materials that remain within the opening”)

• The fifth remaining input is classified in another item; however, this fifth product was together with the other four when the rule was negotiated and now, as a result of the HS update, this restricted product is NOT contained within the heading change (Prohibited materials classified outside new opening).

• Likewise, heading B can receive goods from other headings such as C, D, etc. (Permitted materials classified within the new opening) that did were not restricted in heading A.

• What is highlighted in italics shows the alterations that occur in the composition of the products contained in the heading. Inputs are lost and inputs are added.

• The graph shows us that the products that were required to be originating in a change of tariff heading rule for a product classified in heading A, now classified in the new version of the HS in heading B, are not the same. As a consequence of the correlation or updating of the Harmonized System, the contents of A and B are different.

• If the negotiated rule was a change of heading, and it were to be applied directly to heading B, there would be materials that could previously be non-originating that become restricted, and materials that initially had to be originating that become unrestricted. Applying the same rule is insufficient because it distorts its impact.

Source: Rafael Cornejo. Presentation at the Second Global Origin Conference organized by the WCO from March 10 to 12, 2021

Now, how can we correct the distortion?

• If we want to maintain the requirements of the rule of origin equal to what was negotiated, we must modify the wording of the rule, because if we maintain the same wording (change of heading), we will be, for example, admitting the use of non-originating materials as we observe in case of the fifth input in our example.

• In other words, if we do not adjust the wording of the rule when applying the new version of HS, the scope of the origin requirement (in our example, change of heading) is modified.

Reactions of operators to a new version of the HS

How do the operators act in origin when the HS is updated? The most generalized and certainly incorrect way to resolve the impact of the HS update is “Literally applying the text of the negotiated rule in an old version of the HS to the new opening where the product is classified.” As we have just demonstrated, by automatically applying the same wording, we are distorting and modifying the origin requirements of the product in question, since products that were not restricted in the original rule are being restricted, and/or non-originating materials that were not originally allowed are enabled.

The situation described in the previous paragraph is the most frequent way of working for producers, exporters, importers, certifying entities and customs officials in the vast majority of trade agreements that do not adapt their rules of origin to the new HS version in force. This statement is based on the fact that given the variety of existing correlation alternatives, it is impossible to establish the impacts of the distortions in each operation. That is why it is essential to have annexes of rules of origin updated to the current version of the HS.

To avoid errors, it is necessary to maintain an equivalent and similar level of restriction in the rule of origin in both versions of the HS. To this end, it is essential to analyze the changes in detail, taking into account all the changes produced throughout the update, and not be satisfied with just making the correlation of the subheading in which the product to be exported is classified, as unfortunately is going on in practice.

The impact of the 2022 Harmonized System revision

If we incorporate in our analysis the new version that came into force several weeks ago, we will find two very noticeable situations:

• For the vast majority of subheadings, their impact is similar to that produced in previous HS updates. In terms of origin, the new version will require the addition of an additional conversion, with the aforementioned distortions regarding predictability, transparency and complexity in its use and application. In other words, it will be more of the same, although increasingly with less transparency and facilitating trade less.

• For a limited set of 4 headings, containing 15 subheadings, the impact of the HS 2022 conversion is explosive.

In effect, there are 15 subheadings in Chapter 85 of the 2022 version of the HS where each is equivalent to between 500 and more than 1000 subheadings of the 2017 version. For example:

The creation of new heading 85.49 entails the possible transfer of certain products currently covered by other headings of the Nomenclature (in particular, but not limited to, headings 38.25, 70.01, 71.12, headings of Chapter 84, 85, 90, 91 and 95) to the new subheadings 8549.21 to 8549.99.

In this case of multiple openings of HS2017 that converge in a single opening of the HS2022, we wonder how the correlation will be made to determine each country’s tariffs for third parties, its bound rates, its preferential rates, application of possible tariff quotas, or safeguard mechanisms. For purposes of this blog, what will be the rules of origin? In these cases, not even the erroneous literal application that was previously mentioned will be operationally feasible.

Perhaps this explosive situation will motivate authorities, and particularly the administration committees of trade agreements, to update the available versions of the annexes of specific rules to HS 2022. But while we wait for this change, we find it incomprehensible how little attention has been given to these inaccuracies and the acceptance of the errors that it generates, especially if one takes into account that there are very few agreements with updated annexes of origin available in the previous version of the HS (2017). So once again we ask ourselves:

Why do governments admit, and by default promote, this outdated situation?

Is it a form of permitted violation of the requirements of the agreements?

Do they consider origin requirements to be a second-order issue?

At Origen.Digital we are convinced that it is impossible for public and private operators to correlate the equivalencies in each operation. For this reason, we have developed software for use primarily by governments that facilitates the transposition of the rule of origin expressed in any version of the HS to the 2017 or 2022 versions, and simultaneously drafts text proposals for the rules of origin maintaining the same requirements originally negotiated. On our website you can see a video about how it works (and for those who are interested, we can also offer a demonstration).

In our next blog, we’ll change the subject and move on to discuss another of the rules of origin variables and flexibilities that we mentioned in our initial post. Meanwhile, the comments, coincident or divergent to the contents in this blog are welcome since they will enrich us all. I invite you to share your experiences and your opinions.